Lab Report: Letterpress II: Presswork

Dipshika Chawla

Process Description

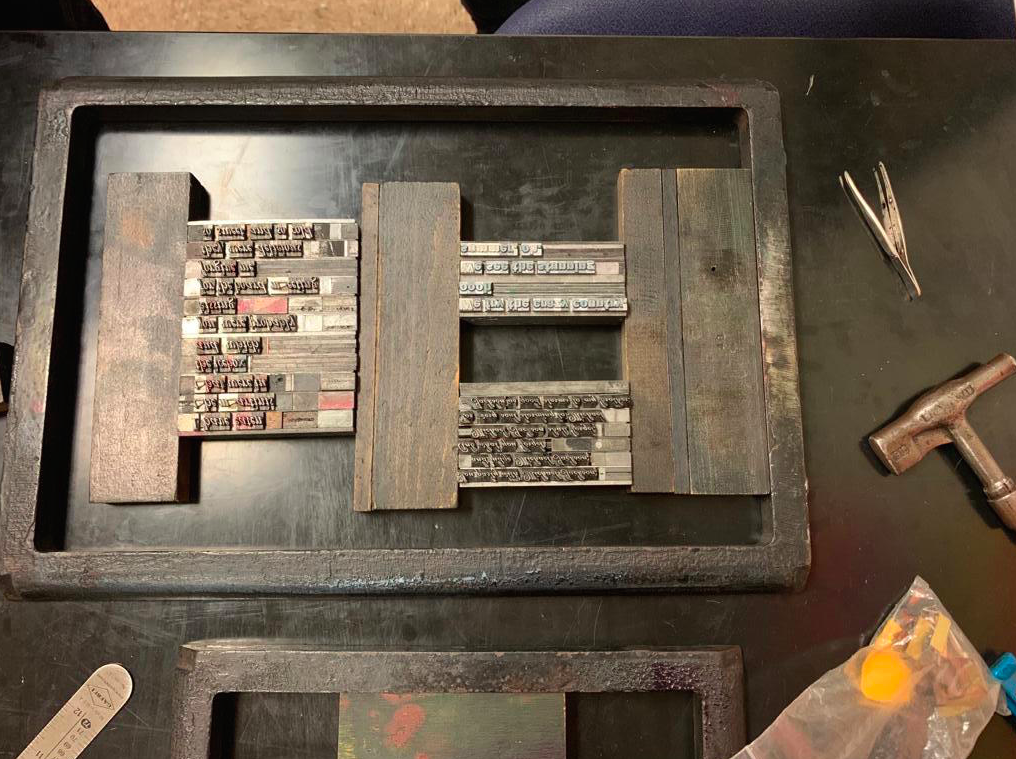

For this lab we focused specifically on the presswork tasks in the greater letterpressing process. At the beginning of the lab, I was still working to complete the composing of the text. Once my composing stick was complete, compressed, and proofread, I was ready to move it over to the chase. This was a particularly difficult task due to the vulnerability of movable type. I felt a great degree of risk when physically relocating the type - the instruction of ‘pressure on all sides’ was perfect in theory, until I had to attempt it for the first time. After the precise placement of type, woodblocks, and quoins in the chase we continued to the room with the press machine. We experimented with double-sided printing, and continued to print 7 copies per student. The hands-on experience with the printing press was an exciting one, and gave me a very holistic and experiential understanding of the reading materials.

Observations

While printing I experienced why printing was not a one-man-job. There were various tasks such as placing paper on the chase bed, running the press by the wheel or pedal, and safely placing printed pages to dry. The tasks required varied levels of physique, movement, and maintenance of rhythm. The physical attributes of the press machine were intriguing and resurfaced the idea of industrialisation of text. It was interesting to see the singular sorts come together, create meaning, lock into place, and transform into consumable knowledge for the world. The final product of printed sheets made the process feel very seamless and one-dimensional, when in reality the printshop has its many nuances and opportunities for creative-solving. It resonated with the idea of how the average person does not think of the technologies of text from the naked eye. The various types of labor - mental and physical - are apparent when doing print work. This was also mentioned in the English Woman’s Journal as the woman’s non-mechanical mind contributing as compositor in the printshop - it exerts a certain type of labor.

Even though text was a growing global phenomena and international structures were forming, the act of printing was ‘local’ in its own way. When we discuss industrialisation of text, it is interesting to think about spelling not standardised until the 18th century, and publishers coming about in the mid-19th century. These primary functions of standardisation and publication are taken for granted and assumed to exist in the modern book. This non-standard approach was also reflected in David Walker’s personalized style of writing and punctuation, and highly expressive pieces of early literature. He used typographic elements and punctuation to his argumentative advantage. Similarly, in the world of pre-standardization, compositors doubled for spellcheckers and based their judgment on phonetics. These were particularly interesting facts, from the perspective of living admist the twenty first century structures in place.

Analysis

As I have noticed in my interactions with letterpresses text, the visual appeal and characteristics of the final product are distinct. As mentioned, the final product makes the process feel very seamless. Similarly, Dinius said the formal intermediate process of print,

Is indeed virtually transparent and so unseen and unpondered; we see only text on the page.

This is true to some extent as readers, especially modern readers, are not consciously thinking of the printing process or book history, as the focus is on book as content and not book as object. However, Dinius also said,

It is impossible to read the words on a page without also reading, albeit usually on a subconscious level, the visual text of the page itself.

This indicates at the reader’s inevitable observation of physical elements of printed text and its typography. We discussed this when looking at impressions of type on printed paper, bleeding ink on double-sided print, and comparing printwork of the past with varying quality. These essentially influence our reading experience and the way we perceive it. Dinius described the role played by typography in by David Walker in Walker’s Appeal as

Using typography to intensify the emotions performed by his surrogate, the printed text.

Leah Price effectively accounts the omnipresence of books over centuries as

A mass-produced object can survive despite a low preservation rate.

The voluminous production of books, technological advancements, enabled dispersion of knowledge, and the integration of print in society, all paved the path for the survival of books across centuries. This ties to the idea of books as containers of knowledge as opposed to expensive objects with limited access. In addition to the preservation of print, we discussed the evolution of how humans perceive print. Leah Price illustrates this evolution in the chapter The Real Life of Books

Just as not all books take the form of print (whether that’s because they’re gorgeously illuminated manuscripts or ruled Mead copybooks), conversely, not all print takes the form of books.

In addition to this physical distinction of text taking the form of the codex or not, she highlights the change in norms of the use and interpretation of text. Price mentions several norms that existed and evolved radically. “From the beginning, printed books were more often borrowed than owned.” This is a norm that existed and is quite foundational to our understanding of the codex, however, she goes on to say how was influenced by nineteenth century publishers and the inverse perspective of sharing books as “immoral or even disgusting.” This stark contrast in our perception of books from two separate time periods is encompassed in the following quote.

The assumption that books are made to be bought is in fact a recent innovation.